Recollections

by

Robert

Darlaston

In

Three Parts:

Memories

of Childhood in Birmingham in the 1940s and early 1950s

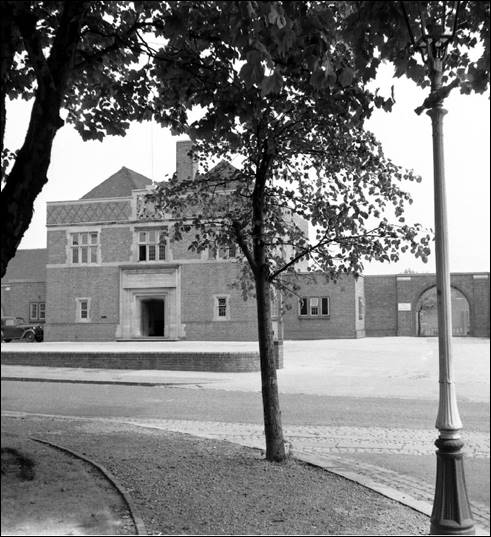

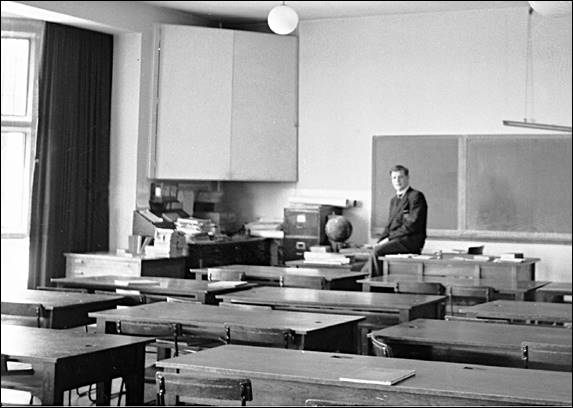

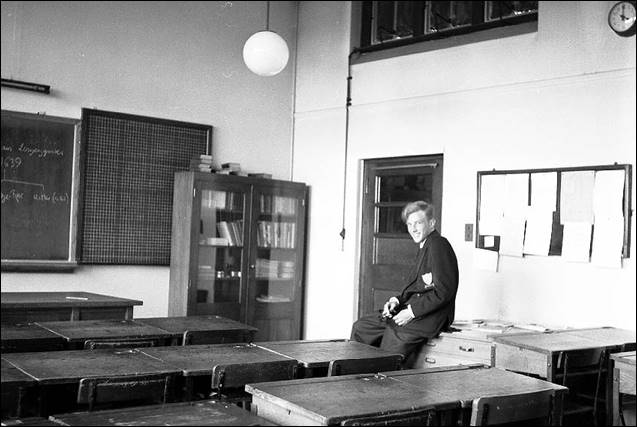

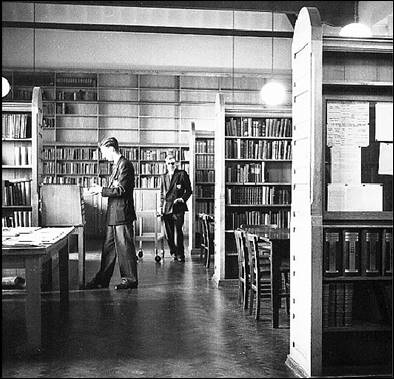

Life

at King Edward’s School, Birmingham, 1951-59, and

Anecdotes

from Barclays Bank Trust Company Limited 1959-97

Illustrated

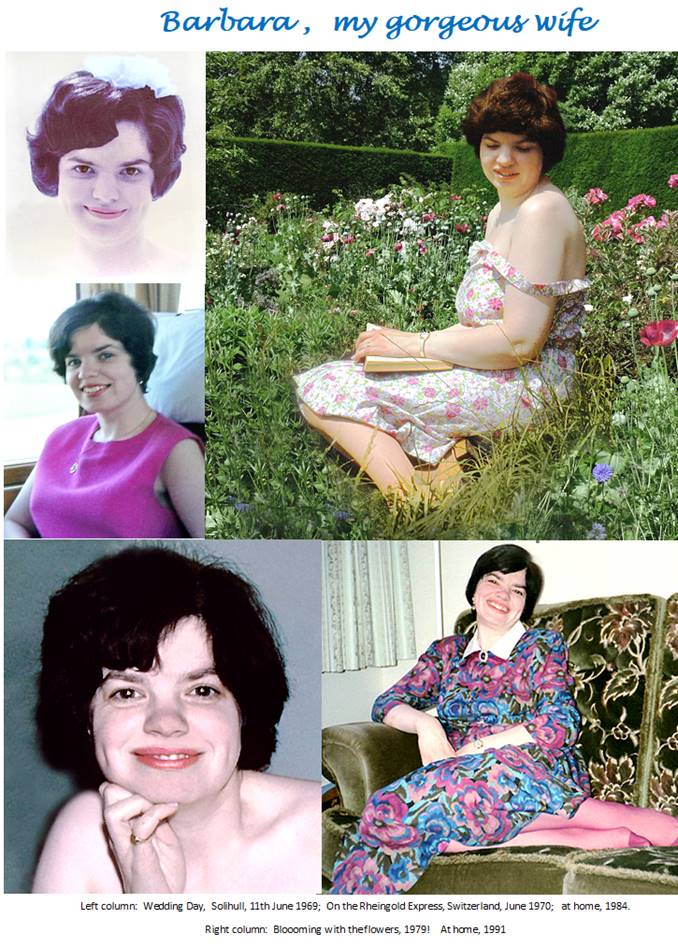

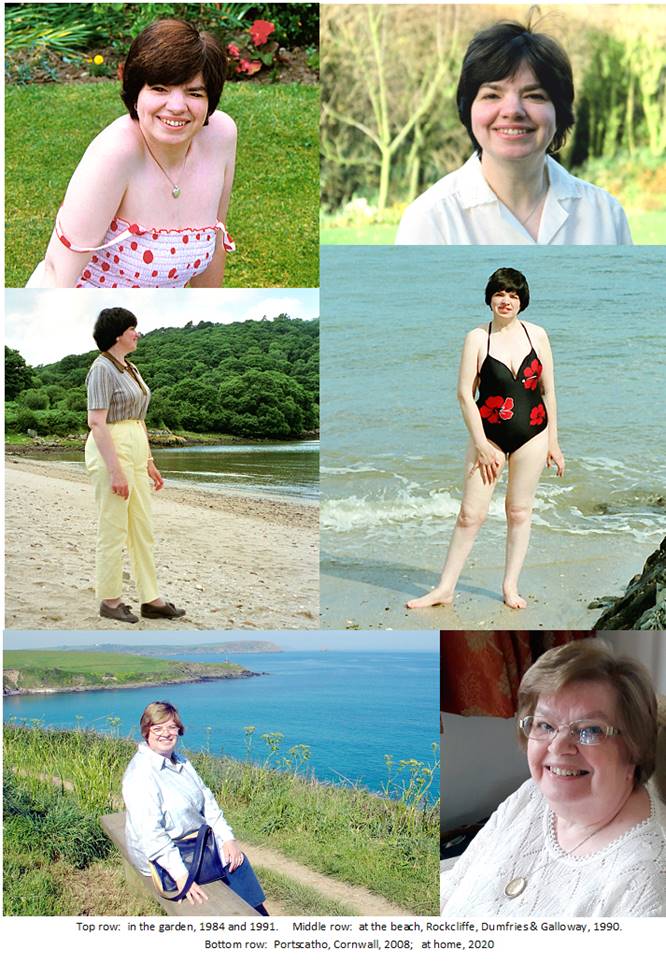

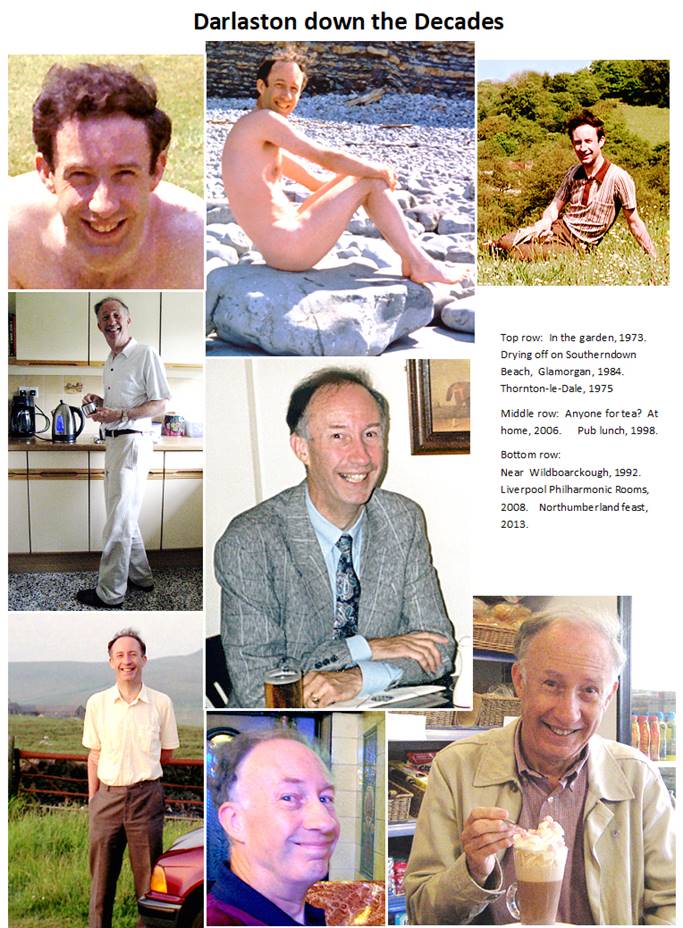

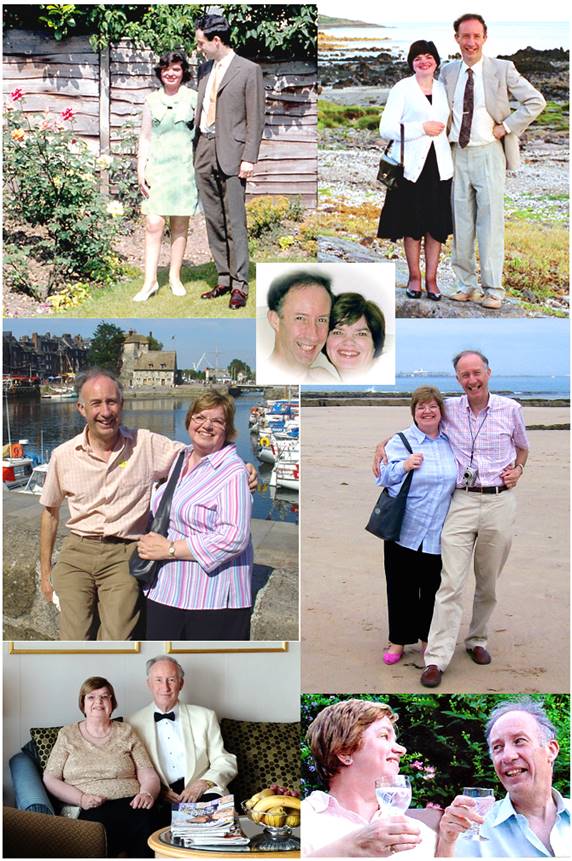

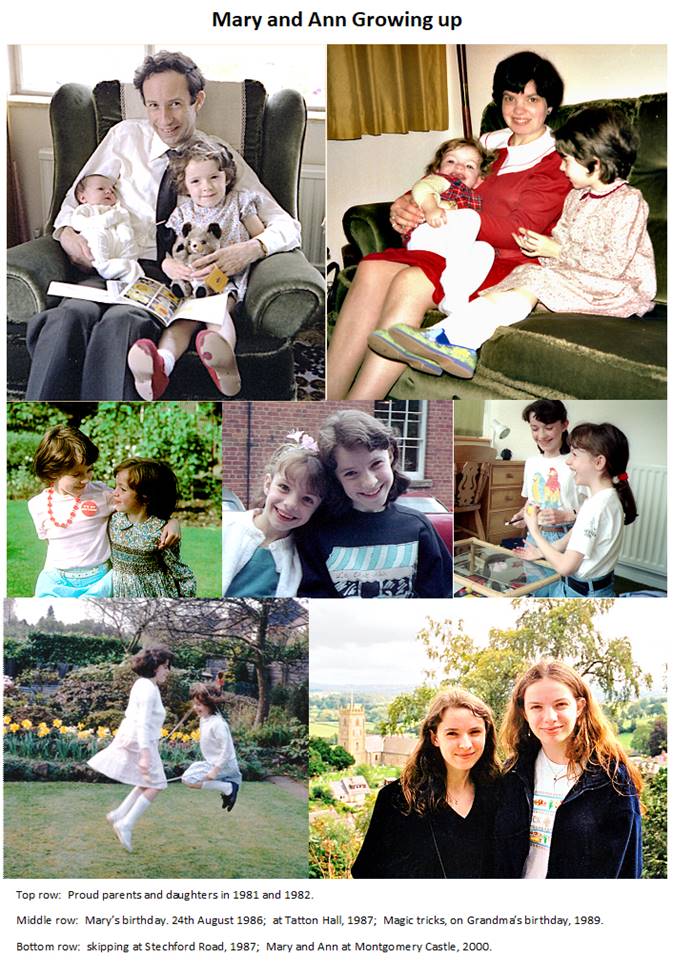

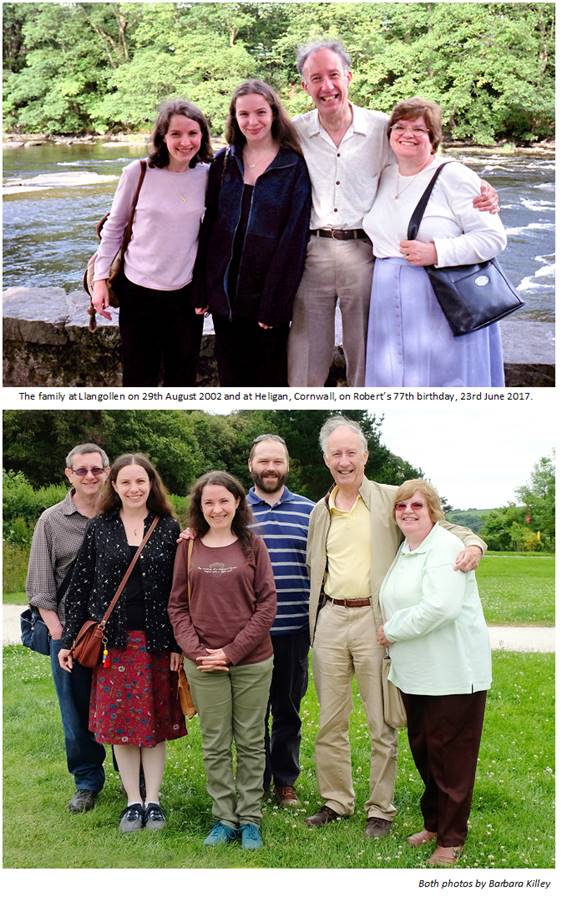

with family photographs throughout

Part One:

Harebells on the Common

A Birmingham

Childhood Remembered

1943 – 1951

First

edition, February 2006

Second

edition, October 2023

Cover

illustrations show the crests of:

The

City of Birmingham (where I lived and worked from 1940 to 1972),

King Edward’s School, Birmingham (attended

1951-59)

Barclays Bank (my employer from 1959 to 1997 -

and who still pay my pension!).

My

childhood home: 165 Stechford Road, Hodgehill, Birmingham

Childhood is measured out

by sounds and smells

And sights, before the dark of reason grows

John

Betjeman

Summoned by Bells

That is the land of lost

content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

A.E. Housman

A Shropshire Lad; XL

Contents of Part One

Early Years My first hazy

memories – 1943

Wartime Birmingham Air

raids; trams

and buttered toast; shopping and the

cinema

South Wales Holidays Farms, seaside and “The Resurrection”

Domestic Life in the 1940s Clothes, wash day,

Christmas and starting School

Worries about Health Tonsils and small boy stuff. Discovery of a chick

A Hard

Winter Snow and fog, 1940s

style

School Days Amberley Prep School;

first glimpse of stocking tops

Children’s Hour Wireless, and Ladies to

tea: I meet the constabulary

A Balanced Diet Meals,

rationing and days out

The King Passes by Glimpses

of the King and of Russian leaders

Changing Times Impressed

by the news and also by Silvana Mangano

A New School Moving to King Edward’s,

The End of

an Era A Festival, a Funeral and a

Coronation

These

pages include some memories of my childhood, dug out of the deepest recesses of

my mind, concentrating where possible on episodes which illustrate how life in

the 1940s differed from that we know today.

I have tried to choose incidents which might amuse, but including topics

both serious and saucy: all part of the

process of growing up in the post-war era!

I hope this account entertains others and ring bells in their own

memories. The 1940s were a grey world

of coal smoke and gas-lit streets, of Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee, Spam*

and steam trains, mangles and woolly vests. There were no mobile phones or DVDs, no

televisions or refrigerators, no foreign holidays or central heating, no computers

and very few motor cars. But it was the only world I knew as a child and I was

well content with it.

(* Spam

was tinned meat and had nothing to do with computers!!)

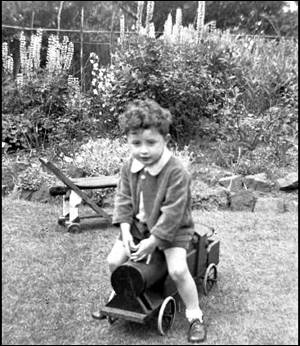

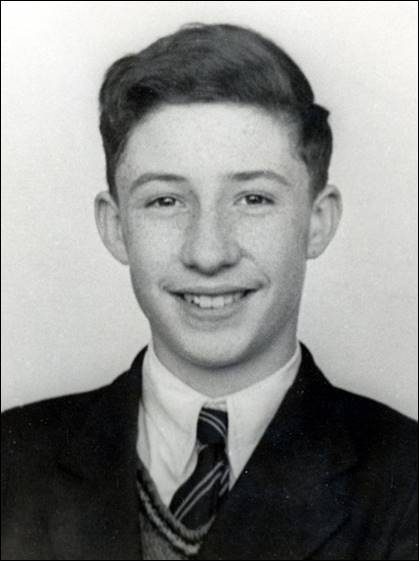

Fifth

birthday, 23rd June 1945.

The

war in Europe is now over and I am sitting on the big red engine made by my

father.

With my parents in the

back garden in 1940 and 1942

|

A |

PRETTY

BLUE LIGHT was flickering, just within reach and looking so attractive, so

tempting. I reached my fingers up to

touch – and: O-U-C-H, “Mumm–e-e-e-e!” The light was the flame of a burner on the

gas cooker which had attracted my innocent curiosity. I would have been only two years of age, but

luckily the impact was fleeting and no lasting damage was done. But the incident remains in my memory as

possibly my earliest recollection. It

was probably early in 1943, a time when others across the world were

experiencing far greater suffering than my rather trivial burn.

Then there was the occasion which stayed in memory as being the first

time I ever saw my mother wearing trousers.

It was the cold night of 23rd April 1943. I was not yet three years of age. The air-raid siren had just gone and my

parents and I were in the dining room, the windows securely covered by the

thick blackout curtains made by my mother, who, in an effort to relieve wartime

austerity, had trimmed the hems with decorative tapes of green and gold. For no particular reason, I was sitting on

the cross-bar beneath the dining table.

We were about to go into the cold night to settle down once again in the

air raid shelter. It is a memory

inextricably tied up with the below-ground smell of damp earth and of the

methylated spirit lamp that illuminated our tiny shelter, built into the garden

rockery. The event can be dated

accurately, because it was the first air raid for several months and thereafter

raids ceased in the Midlands. There are

other associated memories: waiting

before an air raid, the tension tangible in the anxious atmosphere: being told not to suck my thumb after playing

on the floor “because of the danger of picking up germs” – or was it Germans? The words were puzzlingly similar to a

two-year-old.

We cling to our early memories as the starting point of our

life’s journey. The underlying theme

from those days was war: war against a

society so evil it is now hard to realise that it existed in Europe within my

own lifetime. But my parents protected

me securely from that unseen horror, providing an environment of security and

stability. Thus, even though I grew up in

a world of bombs and death, I can look back with nostalgia to a happy childhood. With the exception of my loyal but silent

companion Edward Bear, almost everyone and everything I knew and cherished in

those earliest years has been swept away by the passage of time. But they remain alive in memory, vivid if

intangible, enabling me to make a return journey to my past. There I can once more relive those infant

events and encounters, recreating for a moment the images of childhood.

I was an only child, born on 23rd June 1940 at 1.35

p.m. at

My mother had been born in 1904 and came from Welsh farming

stock, but her mother had died in childbirth.

Consequently, for several years as a baby and toddler she had been

passed around an array of aunts, until, eventually, her father remarried. It must have been an unsettling childhood

for her. She left home at eighteen

years of age and had taken up nursing, first at Newport in South Wales and,

from 1929, in Birmingham. There she met

my father who had been born and bred in the city, although prior to the 1790s

his family’s roots lay in the village of Harlaston,

near Lichfield (hence the family name, originally De Harlaston). My father was born in 1906 and had lost both

parents while still a child, his mother dying in 1915 and his father in 1919. A maiden aunt became responsible for his

upbringing and he was sent to boarding school at Hanley Castle in

Worcestershire, so his childhood too was far from secure and settled.

Castle

Bromwich Church, where I was Baptised.

The Church in snow, January 1963

The

Church is an attractive neo-Classical building dating from 1726-31 and is Grade

I listed.

Like most children, I have many random early

memories: a ride in the pram, a harsh

word here, a tumble there; of the fun

when my father surprised me by hiding in the pantry, and of the panic when I

wandered off to explore alone while my mother’s attention was distracted in the

local butcher’s shop. But unlike the

air raid memories, those cannot be dated.

Then there are those wonderful impressions left in the childhood mind by

patterns; shadows on a carpet; enchanting floral designs on curtains or wallpaper. Wallpaper played a significant

part in my life at an early age. After

lunch each day I was put in my cot for a sleep, but there was a time when sleep

would not come. I lay awake and was

bored. Through the bars of my cot I

could see a small irregularity in the wallpaper. I recall teasing at it with my

fingernail. Oh joy! I could peel a little bit off. A bit more effort and off came another

inch. This was the most satisfying

thing I had ever done. I set to work

with gusto and can still remember the sensuous pleasure of peeling off strips

of paper. Eventually, my mother arrived

to check on her sleeping infant, only to find a joyous child surrounded by

shreds of paper. Suffice it to say that

I was never put down for another afternoon nap.

Paper of a different sort provided further entertainment when my

mother, unable in wartime to obtain the usual brand of toilet roll, bought

instead a box of interleaved lavatory paper (always hard and shiny in those

days). I was fascinated by the

apparently endless supply – pull out a sheet, and, hey presto! – there was

another. Anxious to get to the bottom

of this (sorry!), I kept on pulling sheets until the lavatory floor was

invisible beneath paper and the box was empty.

Once more, I was surprised to find that my mother did not share my

interest in research into paper production.

1943:

Ready to go shopping:

my 3rd birthday: on the big red engine

There

were always Lupins in the garden on my birthday

It is to

my parents’ credit that the nocturnal trips to the air raid shelter caused me

no major worries, other than frustration at my father’s refusal to let me have

a battery in my torch. I suppose he had

an understandable reluctance to let me wave it in cheery greeting to the

Luftwaffe flying overhead. The war was,

despite my own lack of concern, the inevitable background to life and everyone

told me how everything would be “different when the war ended.” News was so dominated by the war that I

believed that when peace came “news” would cease. I now look back, amazed at my good fortune

in being so well insulated from the horrors of those years. My only memories of the end of the war are

of a street party close by and of an unpleasantly hard toffee apple on VE night

at a small funfair erected for the occasion on nearby Hodgehill

Common. Toys were largely unobtainable

until a few years after the end of the war, and magazines would often carry

advertisements for items such as electric train sets, so desirable to a small

boy, but they were marked “For Export Only”.

Consequently, most of my toys were made by my father, including a

handsome wooden train and a soldiers’ fort.

I was lucky that because my father’s work was connected with aeroplane

production he was not liable for military service. He did, however, have to work six (and often

seven) days each week during the war, plus nights spent fire watching. Consequently, he was something of a rare

figure in my early years. Another

result of the war was the occasional visit from a Polish airman, befriended by

my parents and some of their friends. I

was puzzled by an adult whose knowledge of the English language was smaller

than my own.

Some manifestations of war

did cause me alarm. There were sinister

gaps in nearby rows of houses where willow herb grew among the rubble left by

bombing raids. Sometimes an interior

wall was left standing, exposed to the elements, leaving the last residents’

taste in wallpaper for all to see.

There was also the vast ruin of the sauce factory to be seen from the

tram going into Birmingham. One bomb

landed less than 100 yards from home, sucking open the French windows: I was too young to recall the incident, but

the damage to the window frames remained evident until they were replaced

twenty years later. There were baleful

barrage balloons moored nearby on Hodgehill Common

and, from time to time throughout the war, convoys of tanks would pass our

house, driven under their own power, the steel tracks making a deafening racket

on the road surface and sending me scuttling indoors in search of quiet. Worst of all were low flying aircraft, which

terrified me by day and haunted my dreams at night. In 1940, while only a few months old, I had

been in my pram in the garden when a plane came over, flying very low. My mother rushed outside and looked up in

time to see a plane with the German cross and (she said) a Nazi pilot peering

through the cockpit window. She grabbed

me in terror and fled to hide beneath the stairs. (The pilot, probably equally terrified, was

apparently soon brought down some miles away).

Of course I can have no recollection of that incident, but did my

mother’s terror somehow impress itself into my slowly developing mind? Even today, the sound of a jumbo jet

climbing overhead can provoke an involuntary and momentary shiver.

Wartime Picnic with the Godsall family (left) – location unknown, alas

This photo is proof that there

were happy, light-hearted moments during the war.

But suits were still de rigeur, even on picnics!

Jill, sitting between her mother and mine, later became a professional

pianist and remains a friend in the 21st century.

A 1930s postcard showing

Coleshill Road crossing Hodgehill Common.

Less than a decade later, I would

be here picking Harebells for my mother.

But there are

pleasant memories too; of lazy summer

afternoons when I picked Harebells for my mother on the nearby grassy common,

and of shopping trips to town. In “Summoned by Bells” John Betjeman

recalled his childhood as “safe in a world of trains and buttered toast”: in my world trams and buttered toast were the features which linger in the

memory. We went shopping by tram and my

mother always concluded the afternoon with a call at “Pets’ Corner” in Lewis’s

department store, to see the monkeys and parrots, followed by coffee and hot

buttered toast at the Kardomah café. After I started school the trams in their

attractive dark blue and primrose colours became a vital part of my daily

life.

Left: The tram stop where I waited for the tram

home every afternoon after school, (which was behind the hedge at the

left). (photograph by Ray

Wilson)

Right: the lower deck of a tram,

showing reversible seats.

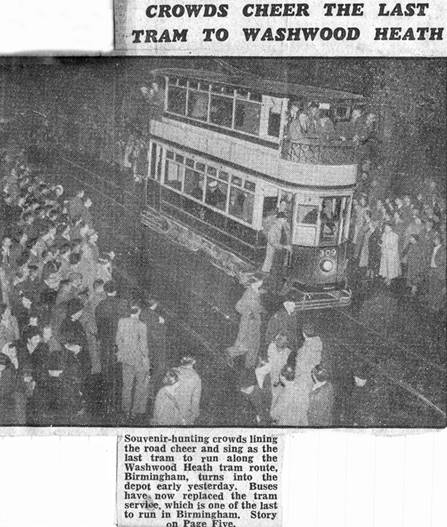

October

1950: The last tram on the No. 10 route,

as seen by the long-defunct Birmingham Gazette.

I had

travelled this route daily on my way to and from school and sorely missed the

trams with their fascinating character:

a souvenir ticket (“Ha’penny child’s”) reminds

one how inexpensive tram travel was in the 1940s.

A special treat in the

summer holidays would be the tram ride to the Lickey

Hills on the Worcestershire border: a

twelve-mile journey across the city, taking over an hour. Tram seats had reversible backs so that one

normally sat facing the direction of travel, but one could leave a seat unreversed

enabling a party of four to face one another as a group, just as on a

train. At the city centre terminus

passengers left the tram at the front while new passengers boarded at the rear. This gave small boys the irresistible

temptation of treading on the driver’s pedal which mechanically sounded the

gong – the tram’s warning equivalent of a motor horn. For the latter part of the journey from the

city to the Lickey Hills the trams forsook the

streets for their own reservation, bowling merrily along through the sunlit

trees at speeds approaching 40 m.p.h.

We would lean happily out of the window, taking care to retreat as other

trams passed close by in the opposite direction. Once at the Lickey

terminus everyone would want to rush off to the hills, but I would try to

linger and watch the conductor placing the trolley pole on the overhead wire

for the return journey; no easy task if

the sun was in his eyes.

Shopping trips

to the centre of

Holidays in South Wales

Wartime holidays

had been confined to annual trips to my grandparents who farmed in

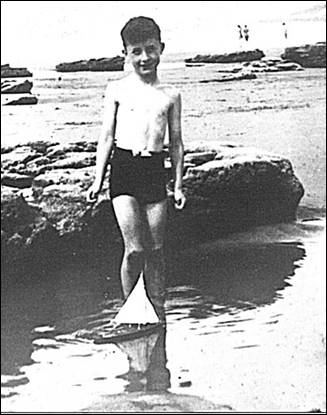

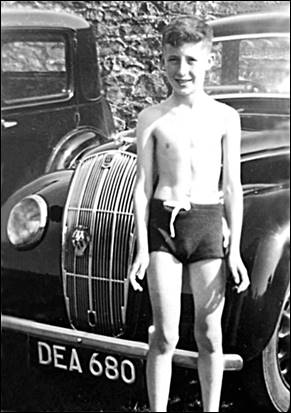

Paddling in a rock pool at Southerndown, 1949;

and by the Morris 8 motor car after changing for the beach in 1950 (note

the old AA badge on the car’s radiator grill).

As a small

child I was bored by the journey to

The wild and dramatic

scenery of the Beacons was, for me, the high spot of the journey as it

signalled our entry into South Wales.

For several miles the road lies above the 1000’ foot contour and at

Easter 1947, after the severe winter snowfalls, only a single passage had been

cut through drifts which towered above our car. On two occasions our journeys were impeded

by serious flooding. By contrast, one

hot day of summer in the early 1950s, we memorably detoured through the Forest

of Dean, passing the historic Speech House, to emerge deep in the wooded Wye

Valley near the imposing ruins of Tintern Abbey. The idyllic situation must have inspired the

Cistercian monks who worshipped there so long ago, just as it inspired

Wordsworth who, after visiting Tintern, wrote of “

the still, sad music of humanity”.

On the way to South Wales: floods near

the progress of a gypsies’ vardo

on 3rd October 1958

At Gilfach

my grandparents did not occupy the traditional farm house, which was deemed too

primitive, but lived in a double fronted Victorian villa (“Oak Cottage”) 200

yards away. This was scarcely any more

luxurious. Electricity was confined to

the downstairs rooms, so I went up to bed by candlelight (logic decreed that as

one only slept upstairs, there was clearly no need for electric lights there!),

and I settled down to sleep with an embroidered text above my bed saying

“Simply to Thy Cross I cling”. There

was no hot water and no cooker: my

grandmother, a tiny, Chapel-going lady, had to rely on the coal fire with a

traditional oven alongside, producing wonderful meals. In the bedrooms there were chamber pots

beneath the beds, and marble washstands with china jugs and basins which would

now be collectors’ pieces. Of the

primitive outside lavatory arrangements at Oak Cottage, the less said the

better. But some farmhouse facilities

were far more exotic, with a long walk to the privy in the orchard where one

might find a commodious building offering accommodation for two patrons seated

on a timber bench side-by-side, and (in one memorable location) even a

three-seater for that special social occasion!

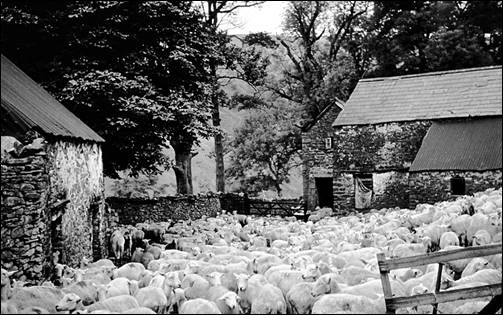

Staying at Gilfach introduced me to farming routines almost unchanged over

the centuries. I would accompany my

grandmother to collect eggs warm from the chickens who roamed free on the

bracken-covered hillside. I would watch

my grandfather with other local farmers as they dipped or marked the

sheep. I would play with his sheepdogs,

who, when they thought duty called, would abandon me and rush off to attend to

the sheep which they found more absorbing than a small boy. On a fine summer’s evening Grandad would put

me on Ginger, his old mountain pony, for a ride up to the paddock: I felt like a maharajah. Grandad was a kind and thoughtful man and

his sheep were almost as dearly loved as his family. In a decade of wars and atomic bomb

development I remember overhearing him say to a farming friend: “I worry about the future for these boys”

(i.e., my cousin and me). How amazed he

would have been at the comfortable and fortunate lives we have led, when

compared with the struggles his generation experienced.

But one Welsh journey in

1945 was alarming. We set off to a remote

Welsh valley to find the farm which was to be the home of Auntie Maud and Uncle

Len, then newly-married. Signposts were

still almost non-existent following the war.

Cloud and fog clung to the mountainside and the drenching rain drifted

across in soaking sheets. As the

Morris climbed slowly into the all-engulfing mist, with a sheer drop of 200

feet at the side of the road, we passed whitewashed signs on the bare rock

face: “Prepare to meet thy God”. Was this to be our final journey? But when we reached Gelli

Farm I found a place which was to me, as a city child, close to heaven in more

childlike ways: 3000 acres of

freedom.

Gelli farm in

the 1950s: A cow approaches, ready for

milking as young riders look on.

In wet weather such farmyards

would be a sea of mud and wellington boots the only possible footwear.

At Gelli

I could escape into a carefree world of the imagination with mountains to climb

and streams to dam – Everest and the Nile lay before me: who cared if my shoes and socks were soaked

through, or if the forgotten chicken’s egg, placed carefully in my trouser

pocket, smashed when I went sprawling in the tussocky

grass? But in those drab, chill

post-war years, the unimaginative adults were more concerned about the lack of

electricity, the enormous fireplace with its chimney open to the sky, and with

the ivy growing indoors on the damp, peeling, farmhouse walls.

Initially Gelli farm lacked any modern mechanical aids and Uncle Len

relied on horses, not just to ride when gathering sheep, but also as everyday

local transport. Once, about 1947, when

we were staying there, he received a message (by runner? – there was no

telephone then) to say there was a dead sheep by the roadside in Abergwynfi. So a

horse (Leicester by name, a rather spiteful animal) and cart were prepared and

I set off with my uncle to retrieve the dead sheep, the only extended

horse-powered working journey of my life!

I was so impressed by the experience I later wrote it up in a school

essay, much to the chagrin of my mother who seemed to feel it reflected badly

on the family!

Throughout

the later 1940s and all through the 1950s my grandfather would stay at Gelli for a few days from time to time to help out at

shearing or other busy times. Horse and

dogs would be essential once he arrived there and began helping with gathering

the sheep. His generation never took to

motor transport, so when it was time to start he would mount Ginger, call his

dogs and they would all set off from Gilfach across

the bleak mountain tops for the twelve mile journey, following the old drovers’

tracks which had been the traditional routes for farmers for many

centuries. To my grandfather this was

more natural than following the motor road round the valleys which was half as

long again and, even then, busy with motor traffic. But farming methods were soon to change,

even in the Welsh mountains, so Grandad was perhaps the last man regularly to

use the old drovers’ roads of South Wales.

Grandad about to set off from Gilfach

on Ginger

Other favoured

destinations when we stayed in South Wales included Barry with its wonderfully

tawdry funfair and its miles of docks, then alive with shipping, and Mumbles

with its electric railway around the bay from Swansea. Nor must one forget those day-long steamer

trips when the Glen Usk,

the Britannia, and the splendid

new Cardiff Queen would take us to

Somerset or Devon, landing us at far away Lynmouth or

Ilfracombe, and once continuing on into the stomach-churning Atlantic swell to

land at Lundy Island.

Visits to

In those childhood days

central heating was almost unknown and only one room in a house would normally be

heated, by a coal fire, although the kitchen might also be warm from

cooking. Thus, for much of the year one

expected to be cold as soon as one moved away from the fire and going to bed on

a winter’s night was an especial ordeal.

So instead of wandering about the house (as is now customary) in

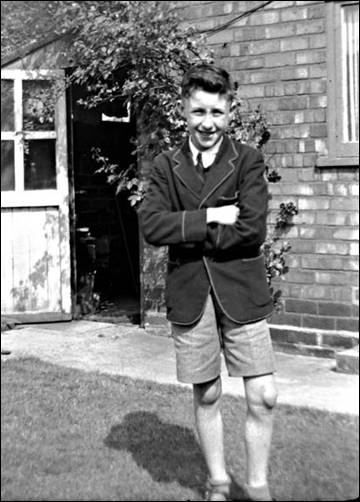

shirtsleeves, I would as a child wear thick woollen underclothes (knitted by my

mother – how did I tolerate wool next to the skin?), a grey shirt of a

substantial Viyella-type material, a long-sleeved

woollen pull-over (also knitted by my mother) and a heavy school blazer. I quickly learned the knack of taking off

pull-over, shirt and vest in one go, ready to be put on in similar manner next

morning, saving time and exposure of one’s skin to the bracing winter morning

air when intricate ice patterns decorated the inside of the bedroom windows.

There were usually two blazers on call:

one was new and too large and was worn to school, the other was old and

too small and was worn about the house and for play. School caps, scarves and gabardine raincoats

were added for out-door excursions in all but the warmest weather (and

sometimes even to the beach if there was a chill wind). By contrast, short trousers were de rigeur up

to 13 years of age. In consequence,

knees, habitually exposed to the elements and to frequent close encounters with

the ground, were frequently chapped and scarred. Older men would hardly ever be seen in

shorts unless on a camping holiday when their appearance suggested they might

be home on leave from the East African Rifles.

With a fire in

only one room, winter Mondays were especially miserable to a child, because

Monday was washday and if the weather was wet the washing would be hung to dry

on a clothes-horse in front of the fire.

I recall Monday, 23rd December 1946 as the longest and

dreariest day of my life. Outside it

was cold and damp. There was steaming

washing arrayed in front of the fire, the windows were running with

condensation and my mother was busy, pre-occupied with ironing and mince-pie

manufacture. The rest of the house was

chilly and unwelcoming. I was bored and

bad-tempered. I wanted Christmas to

come quickly, but time seemed to be at a standstill. Eventually, after what seemed more like two

weeks than two days, Christmas arrived and brought a rarity: a red clockwork

engine, number 6161: no rails, for the

war was but recently over and toy production was limited. Soon after breakfast tragedy struck, for the

engine, on a fully wound spring, shot across the floor like the proverbial bat

from Hades, and wedged itself underneath the sofa, crushing its tinplate cab in

the process. There were tears, but my

father was on hand to administer repairs, and the engine returned to service in

fair, if not pristine, condition.

Presents at

Christmas arrived mysteriously, during the night, in a pillow case at the foot

of my bed until I was thirteen years of age, by which time the identity of

Father Christmas had long since been established. One wartime Christmas, my main present had

been a Golliwog, carefully made by my dear mother, arranged with his head

peeping out of the pillowcase. No

political correctness in the 1940s!

Notwithstanding the war and its associated militaristic attitudes, I was

never allowed a toy gun and once when someone gave me a water pistol, it

disappeared very rapidly. Violence and

aggression were not to be part of my upbringing.

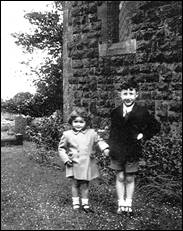

With Jackie: holding hands in 1948!

165

Stechford Road: the new pond in 1949

I had started school in May

1945, shortly before my fifth birthday.

My parents chose to send me to Amberley Preparatory School, a small

private school on Coleshill Road about a quarter of a mile from home, although

it was later to move a mile further away to Ward End. I seemed to get on well, but after a few

months had some sort of minor breakdown (which I do not remember, and which was

never discussed, although I do recall hearing myself described as

“highly-strung”!) Thus, for a couple of

terms I only went to school in the mornings.

I had been attending school for scarcely a year when I was required to

take part in an event which would not have been out of place in a novel by

Dickens. The school was a small affair

in a Victorian house, run by two unmarried ladies, Miss Major and Miss

Ainsworth. Sadly, quite soon after my

arrival, Miss Major was diagnosed as suffering from a terminal illness. At her request, as a farewell gesture, the

entire school (about fifty children) had to process slowly through her bedroom

on the top floor. As children we

accepted this strange ritual as just another everyday event, but my mind now

gives it the quality of an event in a Dickens novel or, maybe, a sentimental

Victorian oil painting, vast and dark:

“Miss Major’s farewell to her young pupils.”

A curious quirk of my early childhood was that for several years

most of my playmates were girls: there

simply weren’t any boys of my age living locally – had something been put in

the water? Names of girls living within

a few hundred yards that still spring to mind include Jill, J’Ann,

Judith, Juliet, Jackie, (all those Js!), Norma,

Wendy, Iola, Lynne, Hazel and Beryl.

Oh, there was one boy, Timothy, but somehow we never hit it off.

Many random memories were

acquired over those early childhood years, often involving smells: lilac blossom and wellington boots, privet

hedges and coke boilers. But when I

was five I experienced a recurrent bad throat with associated nasal

problems. So, in accordance with the

contemporary medical practice of removing all such evidently unnecessary items

of anatomy, I went into the Birmingham Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital to have my

tonsils and adenoids taken out. This

was a major upheaval for one who had so far led a very sheltered

existence. It thus became the first

event in my life to imprint itself on my mind complete in almost every minor

detail, from beginning to end.

For a start, it was unprecedented in those days of petrol

rationing to go into the centre of

But I soon had my

revenge. For the first (and, I believe,

only) time in my life, I got a girl into trouble. On emerging from the anaesthetic I had a

raging sore throat. I uttered those

famous childhood words: “I want a drink

of water.” The ward was under the

control of a Sister who appeared to be related to Wagner’s Valkyries. She told me firmly that I could not have a

drink. A few minutes later a pretty

young nurse passed by. (Even at five

years of age, I could appreciate a pretty girl). I repeated my request and she kindly

produced a drink. Ten minutes later the

Valkyrie flew past and noticed the empty cup (of a celluloid-type material –

ugh!). “WHO gave you that drink?”

she demanded. I remember my reply. Precisely.

Word by incriminating word: “the NICE

nurse gave it to me.” The sharp intake

of breath seemed in danger of making the walls implode. The Valkyrie mounted her invisible steed and

stormed off on a punishment mission.

For the first, but not the last time in my life, I knew I had said the

wrong thing.

In the years following the hospital visit, health matters gave me

several worried moments. I suffered the

usual childhood ailments in turn – Whooping Cough and Chicken Pox one year,

Measles and Mumps the next. But my most

serious health problem in childhood occurred at about seven years of age, when

I was diagnosed with Ulcerative Colitis, which was dubiously blamed on the

bland wartime diet in my earlier years.

It meant that for several years I was not allowed to eat any fruit

unless all the skin and pips had been removed.

A far more serious worry in the 1940s was tuberculosis, then widespread

and often fatal. Our neighbour’s

daughter and the brother of a school friend had both contracted the disease in

their late teens and had been in sanatoriums for many months. Happily, they both recovered, but the fear of

being carted away from my home in such circumstances did not bear thinking

about.

Then there was an absurd worry, typical of the fears teasing a

small boy’s mind in a sheltered and solitary childhood. This began when I noticed a rather personal

difference between me and the other boys who knelt to contribute to the

hospital’s communal chamber pot.

Similarly, I noticed that I differed from my cousin with whom I shared

an occasional bath when he came to stay.

Despite being a subject of immense fascination to growing lads, it was

not the kind of thing discussed in the best circles in the 1940s. But I had overheard talk of children born

with deformities and thus, for several years, I worried anxiously about my

apparent abnormality and whether it had potential for future problems. Eventually, communal school showers revealed

that the difference schoolboys knew as “Cavaliers and Roundheads” was, after

all, not uncommon. It was to be over

fifty years before I learned that in those pre-N.H.S. days the required surgery

had been performed not in hospital, but one afternoon on our kitchen table by

Dr Lillie. There was no anaesthetic for

the infant patient, but the genial Scots doctor had (as my mother tartly observed)

first fortified himself with rather more whisky than seemed advisable for one

about to wield a surgical knife. Such

operations were then encouraged for claimed hygienic reasons and were doubtless

a welcome supplementary source of income for a G.P. I might add here that in accordance with

the prim standards of modesty of the day, I was even longer to remain ignorant

of the far more interesting structural differences between males and

females. My parents had a small female

nude statue on the mantelpiece, but I attributed its lack of masculinity to

natural reticence and decency on the part of the manufacturer. Once, when I was about nine, a girl who was

a playmate persuaded me to strip off for her edification, but, alas, despite

her promises, reciprocal facilities proved not to be on offer, so in an era

when nudity was never seen in public my innocence was long to remain intact!

But in 1946 there was another event of much

greater amusement to a five-year-old than health or bodily matters. The week before I went into the Ear, Nose and

Throat Hospital my mother and I had found a day old chick. It was squatting, fluffed up against the

cold March wind, on the pavement of an otherwise deserted suburban

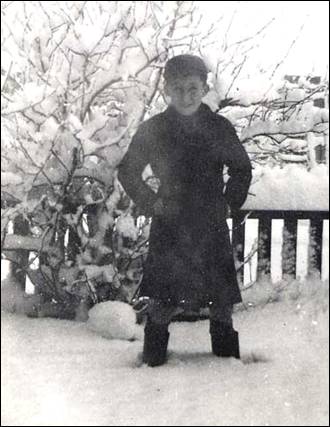

A Hard Winter

No

recollection of the 1940s is complete without mention of the heavy snowfalls of

1947, arguably the hardest winter of the twentieth century. Even in suburban

An

old-fashioned winter: Stechford Road,

seen from our front drive entrance

Dad

clears the drive with Mom’s encouragement and I get ready to build a snowman

Sadly, we have no photographs from the 1947 winter

when snow depths made those shown above quite trivial!

Fog was another winter evil in

cities in the 1940s and 1950s. All

factories, offices, shops and private houses burnt copious amounts of coal for

heating. In still winter weather the

pall of smoke hung in the air and drifted downwards, merging with any slight

mist, to cause an impenetrable fog with visibility cut to ten or fifteen

feet. It would penetrate indoors. Outside, it would paralyse traffic and even

make it difficult to find one’s way on foot.

Most traffic would cease and my father even had to walk ten miles home

from his office on one occasion. We

would be led from school in a crocodile on foot, although occasionally a tram

would crawl slowly through the streets.

A side effect of the fog was that the brick and stone of city buildings

became blackened, and it did not do to inspect one’s handkerchief after blowing

one’s nose!

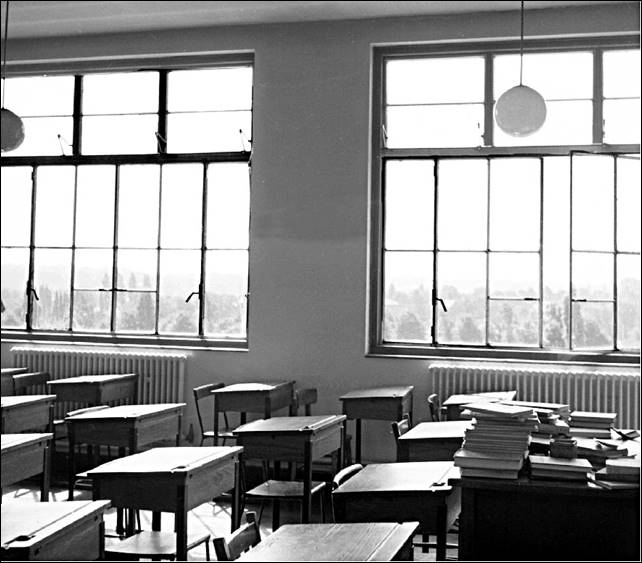

During the hard winter of

1946-7 my school moved to larger premises, permitting a modest expansion in

numbers. The buildings were surrounded

by extensive grounds with shrubberies and winding paths, ideal for the

childhood games of hide-and-seek. Five

to eight year olds were taught in an imposing Victorian house but nine and ten

year olds were housed in a Nissen-type hut built in

the grounds for the Auxiliary Fire Service during the war. The two classes within the hut were

separated only by a pair of large hessian curtains, drawn back at play-time and

for lunch. A large coke boiler provided

the communal heat: a low railing prevented

us from coming into contact with its scalding sides and served as a clothes

horse for damp coats on wet days, thus ensuring that the hut was filled with

the objectionable smell of damp wool mingled with coke fumes. My school life in those days generally

lacked excitement; mile-stones included

the early, tentative, steps in writing and the daily recitation of

multiplication tables and imperial weights and measures (“22 yards make one

chain, ten chains make one furlong”, etc).

Writing at first involved using chalk on miniature slates, but later one

graduated to dip-in pens with which to practice “pot-hooks”. Reading found one exploring Nathaniel

Hawthorne’s Tanglewood Tales, and such old world delights as

Talbot Baines Reed’s Adventures of a

Three Guinea Watch. Art merged with

nature study as we produced seasonal drawings of catkins, sticky buds,

bluebells or autumn leaves. To

discourage us from developing a whiny Brummie accent

we had elocution lessons from the aptly named Miss Homfray. I remember the first poem she taught

us: A

little snowdrop grew in my garden bed,/ All dressed in white / She looked about

/ And shyly hung her head. Those who

pronounced the last line as “Shoyly ‘ung ‘er ‘ead”

failed to impress the demanding Miss Homfray (who

didn’t like being referred to as Miss ‘Um-free).

I managed with little effort to keep

at or near top of the form in most subjects and usually received good end of

term reports, even if they often described me as “fidgety”. The most critical observation (at ten years

of age) was that “he should learn not to make sotto voce remarks”: whatever had I been overheard saying about

one of the teachers? Hymns were

engraved in our minds at the morning assemblies: on the Wednesday nearest our birthdays we

were allowed to choose the hymn. The

girls usually went for “All Things Bright and Beautiful”, “There is a green

hill far away” (why was it without a city wall? – very puzzling when one is

eight or nine), or “There’s a friend for little children above the bright blue

sky”; but the boys generally favoured

“Onward Christian Soldiers”. These did

seem more lively than the dreary “The day thou gavest

Lord has ended” which so often turned up at Christ Church, Burney Lane which my

mother and I attended at rather irregular intervals. Christ Church was a modern building, far

less attractive than the parish church at Castle Bromwich, but much nearer to

home. A Midlands celebrity preacher was

Canon Bryan Green, Rector of St Martins in the Bull Ring in Birmingham, who was

a highly regarded evangelist. Mother

and I went to hear him twice at Christ Church and felt slightly cheated that he

preached the same (lengthy) sermon on both occasions! A local pillar of the Church was a prim

elderly spinster with the appropriate name of Miss Perfect. At about six years of age I was taken to be

introduced to her (rather like being ceremonially presented at Court) and she

commemorated the occasion by giving me a New Testament.

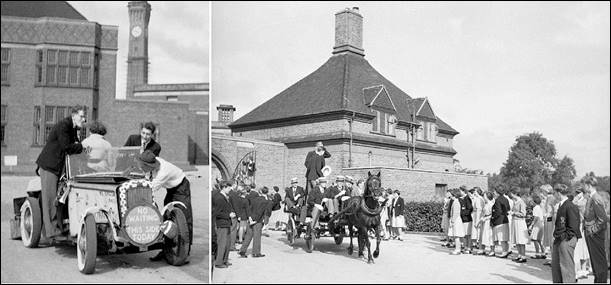

Amberley Preparatory School: Fancy Dress competition at the Church Hall on

Hodgehill Common, Christmas 1948

My mostly tranquil school

life suffered one significant interruption when a girl in the class complained

that another girl, called Yvonne, had stolen her fountain pen. The Principal, Miss Inshaw,

made enquiries and the pen was duly found secreted in the top of one of

Yvonne’s black woollen stockings. The

poor silly girl was expelled, causing a frisson of excitement through the

class. I had not previously encountered

the world of theft and expulsion, nor, come to that, the world of

stocking-tops: sensations all, to an

eight-year-old.

Manners were an essential part of

one’s education in the highly structured society of those post-war years. One did not speak until spoken to. As boys, it was impressed on us that we must

treat ladies with respect at all times, a practice still faithfully kept by

some of my generation. A gentleman

should raise his hat on meeting a lady, should hold the door open for her,

allowing her to go first, and should always stand whenever a lady entered a

room. On crowded ‘buses one should

always offer one’s seat to a lady.

Conversely, real ladies did not go into pubs without a male escort, nor did

they smoke cigarettes in public.

Elocution lessons ensured that we spoke correctly and avoided

colloquialisms, especially “O.K.”.

Swearing in company was almost a capital offence. One might just hear one’s parents say “damn”

or “blast” under serious provocation, but the words were not permitted in a

child’s vocabulary. “Bloody” was used

by men only in the most extreme situations and would certainly never have been

allowed on the wireless. Stronger

language still, nowadays common-place, was largely confined to the working man

in his own environment and would never be heard in public. Just once, a boy called Gilbert used such a

word to me. I asked my mother what it

meant, but she didn’t tell me. I was,

however, forbidden henceforth to go to Gilbert’s house, which was a pity as he

had a very good train set.

Although I had a small circle of

friends at Amberley, much of my leisure time was spent alone, contentedly

reading or playing with my Hornby Dublo electric

train set, or happily riding my blue Hercules bicycle around the quiet

suburban pavements. I am told I learnt

to read when I was three by finding Music

While you Work in the Radio Times!

After Rupert Annuals and Enid Blyton, I graduated to Arthur Ransome books, ‘Bunkle’

adventures and the ‘

My form at Amberley was quite small, about fifteen to twenty

pupils, of whom most were girls. One

young friend was J’Ann Page, who moved to Somerset about

1960, but with whom I re-established contact in 1985 through a neighbour of my

parents who had remained in touch. J’Ann was a lively girl and we often enjoyed a threepenny

ice cream as we walked home from the tram on the journey back from school. But

the world is not yet ready for the curious tale of how her socks came once to

be lodged high in one of Stechford Road’s sycamore trees. In the years 1949 – 1951 two boys in

particular were my firm friends: Derek

Silk and David Yates. On leaving

Amberley we inevitably drifted apart, but happily got together again on several

occasions in the 21st century, thanks to connections made through

the internet. At school, we tried to

pass ourselves off as a “gang”, modelled partly on Richmal

Crompton’s Just William stories and partly on Jennings, with a

dash of Dick Barton – Special Agent, courtesy of the BBC Light

Programme’s serial at 6.45 each evening.

We wore our fashionable “snake” belts, but of our daring exploits little

remains in memory. My most serious

misdemeanour arose when I was “dared” to knock on someone’s door near the

school and run away: I was caught and

Miss Inshaw duly administered a stroke with a ruler

on the palm of my hand, almost certainly the only time in my life that I suffered

such physical punishment. Truth to

tell, the public humiliation was the worst aspect of the incident.

(Schooldays continues below, after Dan Dare)

The view from 165 Stechford Road

The view

looking into Hodgehill Road in the early 1950s, soon

after the introduction of the

55 ‘bus

service in October 1950, but before replacement of the 1930s-style lamp posts

by tall modern lighting. When my

parents bought the house in 1932 it faced open fields with a view to

The view

of the back garden shows the lawn around which I rode my Hercules bicycle,

with the

rockery beyond (into which the air raid shelter had been built for the duration

of the

war) and behind which there was a small vegetable garden.

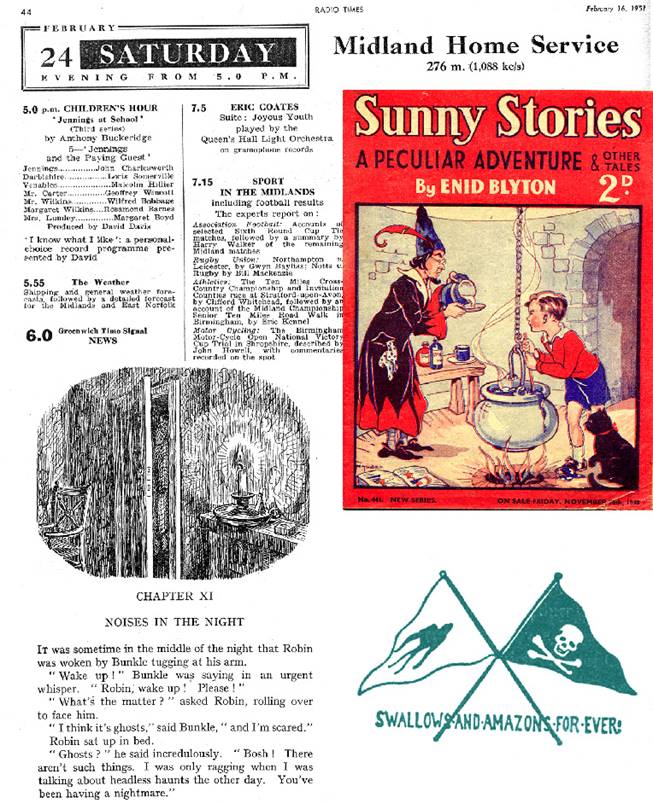

Some childhood souvenirs:

Clockwise from the top:

An

excerpt from Radio Times: wireless programmes for 24th

February 1951, including Jennings

at School;

the cover

of Enid Blyton’s weekly Sunny Stories for November 1948;

one of

Arthur Ransome’s decorations from the pages of Swallows

and Amazons;

a page

from Bunkle Butts In, by M. Pardoe

(1943), with illustration by Julie Nield [The

‘Noises in the Night’ were intruders in the secret passage!]

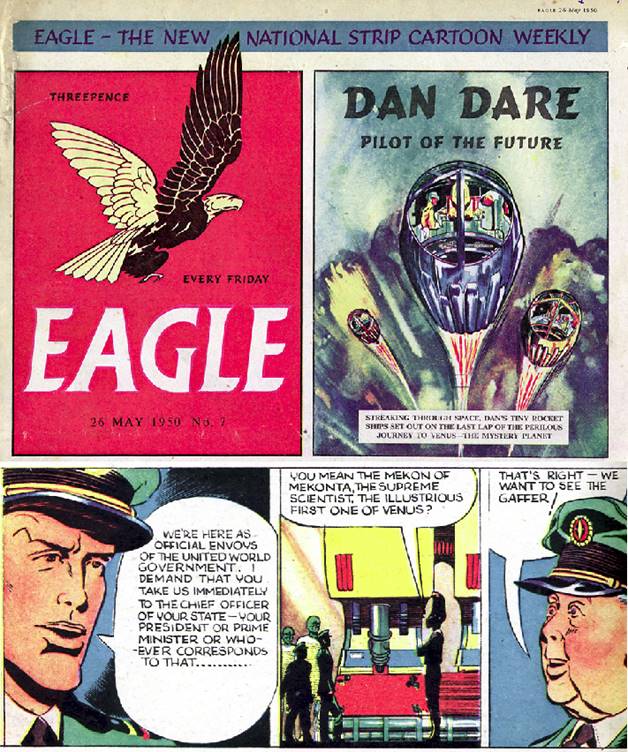

Extracts

from an early edition of Eagle, showing Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future.

Art work, by Frank Hampson, was always of a

high standard; the stories often

contained a discreet didactic element and schoolboys enjoyed the humorous side

as evidenced by the bluff Lancastrian approach of Digby, Dan Dare’s batman.

School days (continued)

Our ‘gang’ got into the local sand quarry one weekend when it

was closed, climbing through a fence near a sign saying “Trespassers will be

prosecuted”. But I was not cut out for

a life of crime and for weeks thereafter I was convinced that every knock at

the door would reveal the house surrounded by Scotland Yard men come to arrest

me for trespassing. In any case, with

my bouncing mop of unruly curls, big brown eyes and (in summer) white ankle

socks I never cut a very macho image.

Another boy in the class was Alan Smith but he was destined not to be

part of the ‘gang’. Sadly, he suffered

from Multiple Sclerosis so he wore surgical boots and walked with

difficulty. He was unable to join in

most of our games. His life was to be

short and sad, but to the rest of us his condition was a fact of life and we

selfishly continued with our games while he looked on. Only later did one begin to wonder what his

thoughts must have been.

Because of the small number of boys,

sport scarcely featured in the school curriculum and, although a few boys liked

to kick a ball about, football was not the obsessive interest it became in

later decades. As an only child I grew

up happily uninterested in games and other competitive activities. Dad did once take me to see Aston Villa play

when I was about seven, but I was hit painfully in the face by the muddy ball

when it strayed into the crowd. The

return home of a mud-splashed and blood-stained child incurred maternal

displeasure, so the trip was not repeated.

There were swimming lessons once each week, involving the tram ride to

Woodcock Street baths. By the time one

had changed – always two boys to a cubicle – there was time for only about

twenty minutes in the water. But

afterwards came the best bit, a cup of hot chocolate and a tiny slice of swiss roll in the café.

School P.T. exercises took place out of doors in fine weather only,

evoking the memory of the row of girls in front bending to touch their toes,

thus providing a momentary glimpse of their navy blue knickers as they leant

forward. A little more exciting was the

occasion during a game of ‘tig’ when I lunged to

touch Angela Moran and inadvertently (honest, guv!) succeeded in pulling off

her wrap-round skirt, thus revealing a tantalising hint of feminine delights –

though in those innocent times that was a country which would remain terra incognita, completely off limits

for twenty more long years.

At ten years of age I

suffered the first pangs of interest in the opposite sex. For a while I took to eating my sandwiches

with one of the girls and we would wander around the school grounds at break

and lunchtime having earnest discussions.

I endured some taunting from my two chums in the ‘gang’ who clearly did

not understand affairs of the heart.

Then, at the end of term, she broke the news that she would be leaving

and so the school “gang” member-ship went back up to three.

Meanwhile, childish fun went on as

before. Birthday parties continued

until I was eleven. Organised by my

mother, there were games, always including “pass the parcel”, then there was

tea (actually Corona “pop” and birthday cake), and then some wild

running about in the garden until it was time to finish. Parties were always mixed, but activities

usually seemed to divide into boys v girls. The girls always wore party frocks and had

ribbons in their hair, looking as pretty as a picture. They would surely have grown up into

wonderfully attractive young ladies, but by then our ways would have sadly

parted.

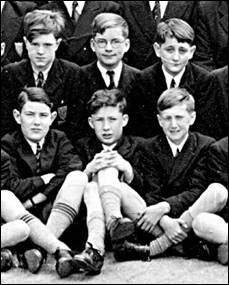

Birthday

party 1951: back left: Derek Silk,

RHD, David Yates,(“the gang”)

back

right: Norma Page, Stella Richardson, Myrtle Pridmore

front:

Keith Hickinbottom, J’Ann

Page

“ Children’s

Hour ”

Out of

school, music was my most lasting discovery of those early post-war years,

destined to develop into my life’s main leisure interest. Ours was not a musical household and I am

told that my favourite piece of music during the war was called “Pistol Packing

Momma”, long since erased from my memory.

But, like most contemporary middle-class children, I was an avid

listener to “Children’s Hour” on the BBC Home Service (no television in those

days!). Many of the items were

introduced by tuneful extracts from classical music, some of which etched

themselves permanently into the mind. Said the Cat to the Dog opened with an

extract from Walton’s Façade and

“Music at Random”, a series of talks by Helen Henschel,

began with the main theme from the last movement of Brahms’s First

Symphony. One serial used Sibelius’s En Saga.

Another drew briefly on the music of Shostakovich, and, with the help of

Radio Times, sent me on my first

voyage of discovery to the newly-developed Third Programme. (I remember, however, being seriously

bewildered by the music encountered there – not for the last time!) At Christmas 1948 I first heard John

Masefield’s Box of Delights with

music from Victor Hely-Hutchinson’s delightful Carol Symphony. Box of Delights was to be repeated in

1955, before being transferred to television in 1984, each time with the same

music. But the piece which I enjoyed

most was one used to introduce a children’s adventure serial broadcast in 1947

called Bunkle Butts In. I was hooked by the first “thriller” I had

encountered (I still have the book!).

The music, Elgar’s Chanson de Matin, entered into possession of my brain and started

me on a lifetime’s enjoyment of classical music. Thanks to the organisers of “Children’s

Hour”, music became an absorbing ingredient of my life when I was just seven

years old. I fear that today’s

youngsters lack such an introduction to the magic of classical music.

There was, of course, other, more light-hearted, entertainment

to be had from the wireless (as it was then called). A favourite was Much Binding in the Marsh with Kenneth Horne, Richard Murdoch, Sam

Costa and Maurice Denham. Lying in bed

on Sunday evenings, I would hear the voice of Frankie Howerd

in Variety Bandbox drifting upstairs,

accompanied by my parents’ laughter.

The most discussed show was probably ITMA

with Tommy Handley who died so suddenly aged 57 in 1949. During and immediately after the war ITMA had been a major factor in uniting

the nation: at a time when there was no

television, and wireless programmes were confined to the BBC Light Programme

and Home Service, choice was restricted and the majority of the population would

be enjoying the activities of Handley and his crew. Billy Cotton’s Band Show on the Light

Programme accompanied our lunch every Sunday, ensuring that I was soon

word-perfect with “I’ve got a lovely bunch of coconuts …”

Television broadcasts had

started in London in 1936 but were suspended for the war, restarting in June

1946. The service reached Birmingham in

1949 and was extended throughout the rest of the country in the 1950s. We acquired our first set in February 1951 at

a cost of 60 guineas (equivalent to £1623 in 2023). Early receivers came in vast wooden cabinets

but had tiny 9” or (for the affluent!) 12” screens. For many years programmes were broadcast

live and went out for limited hours only:

initially there were children’s programmes from 5 pm to 6 pm, and then

nothing was transmitted until evening programmes began at 8 pm, continuing

until about 10.15 pm. My first glimpse

of television was of an old Hopalong Cassidy western

film being shown in the window of a radio retailer: it may have been a flickery

black and white picture, but to me it was then the last word in sophisticated

entertainment. Other early delights

were “Mr Pastry” (remembered installing a TV aerial on the roof and falling

into a waterbut) and the 1951 studio-bound production

of E. Nesbit’s Railway Children – no

actual trains were shown, but steam might occasionally be blown across the

screen!

Evening programmes were

introduced by announcers dressed formally in evening wear: viewers were greeted by Sylvia Peters or Mary

Malcolm in elegant dresses and McDonald Hobley or

Leslie Mitchell immaculate in dinner jackets.

As programmes were broadcast live (even the Thursday repeat of the

Sunday night play was a second live performance) it meant that disasters great

and small reached the home screen. Not

infrequently the screen would go momentarily blank before an elegantly written

notice appeared:

“Normal Service

will be Resumed

as soon as Possible”

The first person I ever

saw drunk was Dr Glyn Daniel on the television programme Animal Vegetable and Mineral – he and his guests had evidently been

celebrating before-hand, rather too well.

My first hint that sex appeal might be of some significance came about

1952 in a live programme with the elderly artist Sir Gerald Kelly talking about

(I think) Fragonard's "Girl on a Swing": he suddenly turned to the camera with a

wicked twinkle to add a daringly unscripted remark: "Look at that lovely little

bottom". My mother laughed, then

remembered I was there and said "Well!!" in a certain tone of voice.

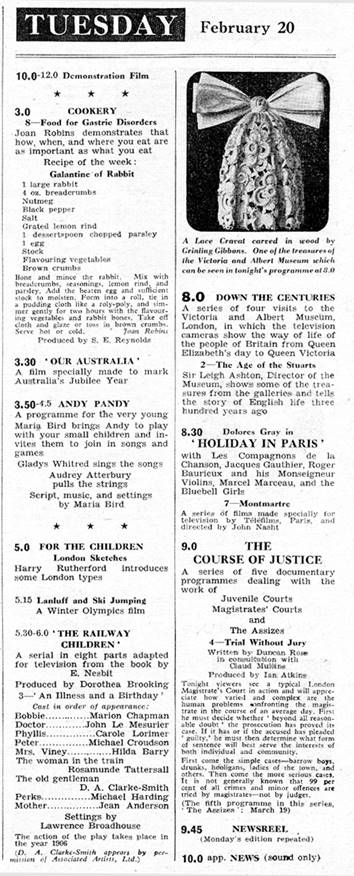

A sample of television programmes from 1951

An

extract from Radio Times showing all the television programmes for Tuesday,

February 20th 1951

It will be noticed that no

programme were broadcast between 4.5 and 5.0 pm, or from 6.0 to 8.0 pm.

Following the News (sound only)

television closed down at about 10.15 pm.

The death of

radio’s Tommy Handley was an uncomfortable reminder of human mortality. During the 1940s two neighbours died,

comparatively young, raising in a child’s mind the question of our ultimate

destination. The mother of Juliet

Powell, a little girl with whom I had sometimes played, died in her 30s from

breast cancer, and “Uncle” Bill, our next-door neighbour died from pneumonia in

his mid-fifties. These events raised

uncomfortable questions, but children look ahead, not back, and the events were

soon all but forgotten. The equally

great mystery of birth surfaced from time to time: I remember asking my mother where I had come

from, but I cannot now recall her reply which was doubtless a masterpiece of

dissembling! But I was temporarily

satisfied, without the destruction of childish innocence which now seems to be

the rule.

Much of my knowledge of

life’s caprices came from unintentional eavesdropping on my mother’s

conversations with her friends. She led

a life ordered by routine: Mondays were

for washing (morning) and ironing (afternoon), Tuesday and Friday mornings were

for local shopping, Wednesday and Thursday mornings were for cleaning –

downstairs and upstairs, respectively.

Except on Monday, after an early light lunch she would change into a

smart day dress. The afternoon was then available for seeing

friends, equally elegantly attired in smart frocks, or for an occasional trip

to the centre of Birmingham. There she

would shop for clothes (although that was limited because of the need for clothing

coupons), or perhaps take me to a matinee at the cinema. When her friends came for tea I would often

sit quietly reading in a chair in the bay window while the ladies sat talking

by the fire. Perhaps I was invisible,

because I would hear remarks about life, husbands and acquaintances which were

surely not intended for me! There was

probably nothing slanderous, but I do remember being amused by mimicry of a

local lady with an affected way of speaking who was quoted as saying “My de-ah,

it took me two aahs to arrange the flaahs.” [Two hours to arrange the flowers.] I felt uncomfortable (and still do) on

hearing a woman complain about her husband’s alleged domestic

inadequacies. I have never heard a man

complain about his wife, suggesting that ‘cattiness’ is indeed a female

attribute! In the 1940s the two sexes

lived quite separate lives: it seemed

men went off to kill or be killed fighting wars or, if living at home, set off,

trilby-hatted to work from 7.30 am to 6 pm each day. On Saturday afternoons they went flat-capped

to football, and spent any remaining spare time caked in mud from digging the

garden or covered in oil after overhauling the car (which probably entailed

lifting out the engine). Women shopped

occasionally, cleaned from time to time, did a little knitting or embroidery,

dead-headed the roses and spent the rest of their time reading to their

children or drinking tea with friends:

it seemed to me an enviable existence compared with their husbands – but

things for me turned out differently and I have no cause for complaint!

In the 1940s and 50s ladies still

had a very different approach to life from men and they cherished attitudes

which their 21st century successors would repudiate. Like most of her sex, my mother, her sisters

and her friends all strongly disapproved of football and all other games apart

from tennis, which was enthusiastically supported. Cricket also enjoyed a limited following

amongst a few of the fair sex. Wives

reluctantly tolerated their men attending football matches on a Saturday

afternoon, but the male obsession with the game was regarded by them as a clear

indication of men’s inferiority to women.

Likewise, it was accepted that men drove cars, buses and lorries: but no self-respecting lady would allow

herself to be seen indulging in such activity.

Their avoidance of motoring was quite sensible in the 1940s as vehicles

were far from reliable and breakdowns and mishaps were commonplace with

“D.I.Y.” repairs often being the only practical solution, albeit tricky and

dirty. A few women did learn to drive,

but they were a tiny minority and regarded with acute distrust by men and even

by most other women!

Life continued with occasional unexpected

twists and turns. In the late 1940s I

experienced an encounter with the constabulary which was to make a lasting

change in my life – although happily without any charges being brought! During the course of a visit to the family

in South Wales, my father had the misfortune to run down a lady who foolishly

stepped off the pavement in Tonyrefail without first

looking to see if the road was clear.

Happily, the car was only travelling at about 20 m.p.h. and no serious

injury was caused. Nevertheless, it was

necessary for my father to call at the village police station to make a

statement. While he and my mother were

thus engaged I endured a very long and boring wait. The sergeant’s wife took pity on me and

brought me a mug of strong tea. This was

alarming, as I disliked tea intensely and never drank it. But clearly one did not argue with the

police. So I braced myself and took a

sip. Heavens! – I liked the stuff! From that day forward I have never refused

the chance of a cup of tea – thanks to the Glamorganshire Constabulary.

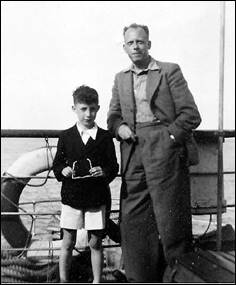

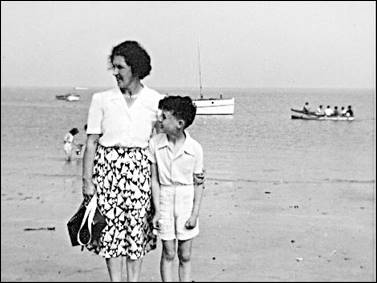

More memories of holidays in South Wales:

With Dad on board the Cardiff

Queen at

Ilfracombe 1949

and with Mom at Tenby after

a boat trip to

Paddling with cousin

David at Llansteffan, Carmarthen, 15th

August 1952.

School blazers and ties

are in evidence, - but not trousers!

When it

came to food there was no opportunity to indulge in the whims and caprices of

taste. Rationing and shortages

continued well into the 1950s and many popular items were simply unobtainable. One had what one was given or went without. Imports of bananas were discontinued

throughout the war and oranges were available only in very limited

quantities. I recall my first post-war

banana as a serious disappointment: I

think I was expecting a bigger, sweeter, more luscious orange. Domestic freezers and refrigerators were

almost unknown, so frozen foods were simply not available until limited

quantities of ice cream began to appear once the war was over: at first in vanilla flavour only; wafers three-pence, cornets four-pence, tubs

sixpence!

Dinner menus were limited in range. Beef, mutton and pork were the staples; lamb was seasonal and chicken a luxury for

Christmas only. Cod, tripe, hearts and

brains appeared occasionally. Meat was

accompanied by fresh vegetables according to season – my diet of green

vegetables was limited mainly to fresh peas out of the garden in July, runner

beans in August and cabbage for the rest of the year, varied only by occasional

carrots or cauliflower. Tinned peas were

available, but were not especially palatable.

In an era of shortages, leftovers were recycled so that yesterday’s meat

reappeared as rissoles, vegetables as “bubble-and-squeak”, and an unwanted tea

might re-appear as bread-and-butter pudding.

Cheese was rationed to two ounces (of non-descript Cheddar) per person

per week. Eggs were scarce, but dried

egg was available for cooking and could even be made into a sort of omelette,

though my mother looked down her nose at such contrived dishes. She baked her own cakes; otherwise we would

probably have gone without. The season

for locally grown fruits was extended by careful storage of cooking apples,

giving the spare bedroom a characteristic smell, and my mother would be busy

bottling plums and damsons in Kilner jars at the end of each summer. Imported tinned fruit was unknown and I did

not taste any until a rare tin of pineapple chunks, hoarded from before the

war, was produced at a family party, held at my father’s old home in Erdington,

for Uncle Cyril who was on leave from the Army. Foreign dishes such as pizza, lasagne, or

paella were quite unheard of; indeed, in

an era when foreign holidays were almost unknown our family would not have

recognised the words! By comparison

with present-day menus it seems a poverty-stricken up-bringing. But the choice was planned in response to

government dietary advice and ensured a generally healthy population. There was no chance of over-indulgence, so

my friends were a skinny and active lot, obese children being unknown!

Sweets were taken off the ration on 24th April 1949

(remembered as being my play-mate J’Ann’s birthday),

but before I could get to the corner shop for a quarter of Barker and Dobson’s

Barley Sugar or of Wilkinson’s Liquorice Allsorts, panic buying by the public

had cleared the shelves nation-wide.

This resulted in the government re-imposing rationing for three more

years, frustrating the dreams of many children who were thus strictly limited

to one or two sweets a day. But in

compensation there was Christian Kunzle’s restaurant

in Union Street with its delicious Swiss-style cream cakes rich with cream

inside a chocolate ‘boat’: one greedily

eyed a plateful but could seldom manage more than one! How strange that such indulgent fare has

long since vanished from the shops!

Food rationing continued with full

severity for several years after the war.

The system demanded that one was registered for food with a specific

shop. Making purchases elsewhere was

not permitted. We patronised Ehret’s, a small grocer (with a surprisingly Germanic name

for those days). There, my mother’s

order was taken over a long counter with a chair placed alongside for the

customer to rest her legs. Many items,

such as butter and sugar were parcelled up on the premises and biscuits

(plain; no cream varieties) were sold

loose from large biscuit tins, pre-packed goods being almost unknown. My mother’s purchases would be delivered

later by bicycle. I always wanted her

to call in at the Co-op, despite not being registered there, as the Co-op had a

marvellous aerial ropeway by which the cash was sent by the shop assistant to

the lady cashier who returned any change by the same means – a fascinating

contrivance for a small boy to watch in action! (The Midland Educational book shop in

A postcard view of

Corporation Street, Birmingham, at the crossing with Bull Street, about 1949.

The buildings behind

and beyond the tram (which is heading for the Fox & Goose terminus at

Ward End, see below)

were replaced by Rackhams’ department store in 1960.

In the late 1940s our rations were slightly

supplemented – unofficially - with the help of Aunty Rene, a cousin of my mother’s who, like her, had left South Wales and settled in

Warwickshire. She and her husband ran

the village shop at Broadwell, near Southam and about twice a year we visited her, returning

laden with contraband packets of Weetabix, bags of sugar, slices of fresh ham

and pats of butter. Broadwell

was then a tiny isolated village lying in a hollow, populated mainly by

agricultural labourers who lived near the poverty line. Most houses were down-at-heel and there was

an overwhelming and unpleasant smell which offended the nostrils as soon as we

got out of the car. Explained by my

mother as “stagnant water”, I later discovered the smell was that of the

village’s cesspits. On our visits I

often played with Margaret, Aunty Rene’s granddaughter and my second cousin

once removed. She was a tall, lively

girl, only a little younger than me.

But in her twenties she suddenly suffered a brain haemorrhage and died,

leaving two tiny children. Aunty Rene

herself died in 1960 and thereafter we had no reason to return to Broadwell. But in

1990 I was driving nearby and decided to make the detour to see how the village

had changed. In thirty years the

down-at-heel cottages had been transformed into “desirable executive commuter

homes”, each with a BMW or Mercedes outside.

The old shop was no more, but was now the largest and most impressive of

all the houses. I might add that the

air was sweet and of the smell there was no evidence.

The Fox & Goose

shopping area, about 1949, from the pages of the Birmingham Weekly Post.

In the left foreground is the Washwood Heath Road with trams on their reserved

track. Alum Rock Road merges in the

right foreground. The Beaufort Cinema

is just above and right of the traffic island.

The Outer Circle route crosses from left to right and Coleshill Road

continues into the distance toward Hodgehill Common,

just visible where Coleshill Road bends left into the trees. Centre-left are playing fields, now occupied

by a super-market. The sand quarry is

visible right of centre: it was later

filled in and became Stechford Hall Park.

Rural Castle Bromwich stretches across the top of the photograph: Shard End was still just a planner’s dream.

Petrol was still rationed well into

the 1950s, so outings by car were strictly limited. On a couple of occasions, when my mother

evidently wanted an afternoon to herself, she would pack me off on the Outer

Circle ‘bus for the two hour circumnavigation of

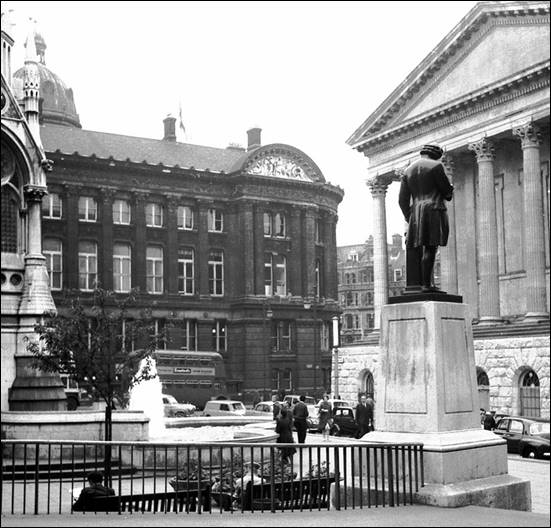

Chamberlain Place,

Birmingham: A Midland Red ‘bus passes

the smoke-blackened Council House as it approaches the Town Hall.

Most stone buildings were then blackened by the smoke in

winter fogs. As atmospheric pollution

diminished in the 1950s the buildings were cleaned, revealing that the stone

had a natural light colour - much to the surprise of my generation!

In the

late 1940s and 1950s the British Industries Fair (“BIF”) was held for two weeks

each summer at Castle Bromwich, only a mile from home. I was taken there on several occasions, even

though the displays of heavy engineering which were the essential feature of

the show were hardly riveting stuff, either for me or for my mother. But there was usually an exhibit featuring a

small gauge industrial railway, intended for use in quarries or on building

sites and the promoters were generally more than happy to demonstrate its cargo

carrying capacity with a load of small boys instead of the more usual tonnage

of granite. In 1947 the BIF was

officially opened by H.M. King George VI, and after the ceremony he was taken

by motorcade to join the Royal Train at Stechford station, so passing our

house. This was an occasion when we

watched from our front garden as the King drove past – I was surprised to find

that there were other, lesser, mortals whose front gardens were not thus

honoured by His Majesty. I will add

here, although it belongs to a slightly later stage of my life, that in 1956

the Russian leaders, Khrushchev and Bulganin likewise were driven past our

house when returning to catch their train to

1950: 10th birthday

For

the most part, news in the 1940s passed me by, but from conversations overheard

between adults, from wireless news bulletins and occasional newspaper

headlines, I gained some vague impression of the drift of events. In 1945 I knew from the VE celebrations that

the end of the war with

In

1945 I had remained in ignorance of the general election which brought Clement

Atlee’s Labour party to power but I soon noticed some of the cosmetic aspects

of Labour’s policies and became familiar with such names as Stafford Cripps,

Herbert Morrison, Ernest Bevin and Aneurin

Bevan. My father admired “Ernie” Bevin,

but Bevan was especially unpopular with both my parents who referred to him as

“Urinal Bevan” although the joke was lost on me. Labour’s nationalisation of collieries and

railways first manifested itself to me by the closure of the tiny private

colliery known as “The Squint” in Gilfach Goch, near my grandparents’ home. Then the familiar chocolate-coloured paint

on Great Western Railway carriages gave way for a while to red, and I vividly

recall the first occasion when I saw a steam engine lettered “BRITISH RAILWAYS”

instead of the familiar “GWR” – much to the disgust of my father.

For

a decade after the war, paper shortages resulted in newspapers comprising no

more than six pages and there was thus room only for one or two

photographs. But the press could always

be relied on for front page pictures of a disaster, so air and rail crashes

seemed to loom large. The horrific air crash in March 1950 near Cowbridge in Glamorgan, when 80 rugby football supporters

returning from a match in

It

now comes as a surprise (even to those of us who were there at the time) to be

reminded how innocent and ignorant children in the 1940s and 1950s were about

matters relating to sex. Parents and schools

shyly dodged the issue. Newspapers,

magazines and the broadcast media never mentioned the topic. Nudity was quite unknown, save for

discreetly-posed black and white pictures in a few “pin-up” magazines which

were not widely available and certainly unknown to me. Boys and girls could thus grow up in a state

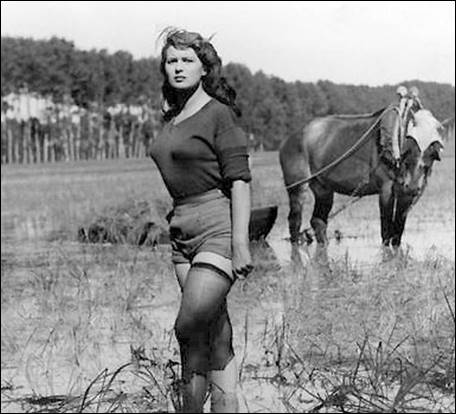

of blissful ignorance of the change adolescence would bring: nothing was said. My own innocence was signally disturbed at

ten years of age by a 19-year-old Italian film actress, Silvana

Mangano who appeared in an Italian film, Bitter Rice, released in Great Britain

in 1950. The publicity photographs for

the film included one reproduced in our Daily

Mail showing Miss Mangano standing in water,

wearing tiny shorts and a figure-hugging black sweater. Never before had I seen anything quite like

it: the picture fascinated me and

brought an exciting sensation, strange and delightful yet a little alarming; new to a growing boy. Thus began five years of change, as I

discovered delight in watching a pretty girl pass by.

Boyish curiosity and flamboyance amongst my contemporaries offered

patchy enlightenment (as well as worrying fables of blindness or worse) but I

was approaching fifteen years of age before the story took shape. Only then did I properly understand that

such bodily developments were to do with reproducing the species and so had

more significance than just to provide passing amusement for teenage boys. The years passed, and other sex symbols such

as Marilyn Monroe and Brigitte Bardot came to tantalise the mind and body of

this adolescent boy, but I shall never forget Silvana

Mangano oozing temptation in a rice field. What a contrast between our own ignorance in

the 1940s and 50s and the obsessive attitudes of the 21st century.

Silvana Mangano

in Bitter Rice, 1949.

She

appeared in several more films, of which the best known

was Death

in Venice in 1971. She died in

1987.

This was the

photograph which caught my eye in the Daily

Mail in 1950.

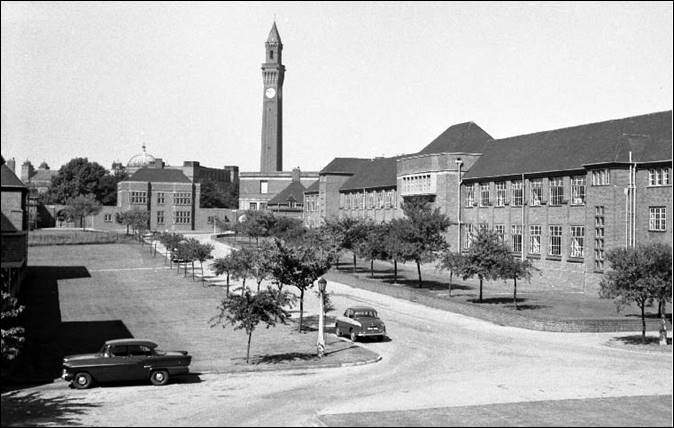

In 1951

I passed the “eleven-plus” examination for King Edward’s School, Aston, but was

also entered for the separate examination for the ‘parent’ King Edward’s School

in Edgbaston. This was a tougher

proposition but I passed and so the lengthy cross-city journey would be part of

my life from September. I would notice

a change: Amberley was a tiny, informal

affair, run by a handful of local ladies, of whom Mrs Bunker and J’Ann’s mother, Mrs Page, were my usual teachers, aided by

Mrs Woodwiss who taught History and Geography on

Thursdays and Fridays only. For a

couple of terms, there was a small sensation when they were joined by a man, Mr

Luby. At

Amberley I was a big fish in a very small pool, but at King Edward’s I would

find myself a very small fish indeed.

The culture shock would be significant.

Instead of the company of a small number of girls and an even smaller

number of boys, there would be 700 pupils, many already grown men over six feet

tall. Life at King Edward’s would bring

testing new subjects including Algebra and Latin to puzzle my mind, and games

such as rugger (about which I knew nothing).

But this new existence would one day cease to be strange and would

itself become second nature.

The early ‘fifties were marked by

three events of national significance:

the Festival of Britain in the summer of 1951, the death of H.M. King

George VI in February 1952, and the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June

1953. These printed themselves on my

memory in different ways. I remember

the Festival firstly for the journey up to

The death of the King was, to a

child, quite unexpected, the news reaching my form at lunchtime as we waited to

go into the school dining hall. After

the colour and fun of the previous year’s Festival, the state funeral itself

had an overwhelming and numbing sombreness, awe-inspiring even to an