This Web Page is Birmingham Pictorial, updated, 10th December 2013

All photos © Robert Darlaston

PLEASE ALLOW TIME FOR PHOTOS TO DOWNLOAD

The

suffering from much damage and

neglect during the war years.

There were corners which were

pleasant enough, but no one would have called the city attractive, colourful or

vibrant.

That was the place we left in the

early 1970s.

Today, when we go back to see old

friends we are struck by the changes since those days.

These photographs were all taken on

such ‘tourist’ visits and show that the once boring old industrial city in the

Midlands

is now, in fact, a place of

considerable interest and style.

Left: Queen Victoria’s statue in Victoria Square,

with the Town Hall beyond.

Left: Queen Victoria’s statue in Victoria Square,

with the Town Hall beyond.

Central

Birmingham:

Panorama of Victoria Square: the

former GPO building is at the extreme left, then the

Town Hall designed by Joseph Hansom and based on the

Left:

The Council House; right:

looking across Victoria Square towards Waterloo Street.

Chamberlain Square with the Art

Gallery entrance at the left and the rear of the Town Hall to the right.

The

Two more views with the Town

Hall: left, towards the Art Gallery entrance (beneath the clock tower)

and, right, across what was once

Ratcliff Place, where now Queensway emerges from a tunnel beneath the 1960s

Library.

Left:

Summer in Colmore Row, looking towards Snow

Hill station, with the Cathedral Precinct to the right.

Right:

Christmas in the Great Western Arcade, built over the cutting taking the

Great Western Railway company’s line into Snow Hill

station.

Left:

Looking up Corporation Street from the entrance to New Street

station. At the left is the former

Midland Bank building which has since become a remarkably palatial branch of Waterstone’s bookshop.

Right:

Waterloo Street, built at the time of

St Philip’s Cathedral, dedicated in

1715 and designed by Thomas Archer, is based on the baroque churches of Bernini

and Borromini in

Two more views of the Cathedral

The Bull Ring:

Nelson looks down on the Bull Ring,

as he has since his statue was erected in 1809. But now he stands before the futuristic

Selfridges’ department store, which looks exotic by day and even more so by

night.

The Bull Ring gained its name from

bull-baiting which took place there about 700 years ago.

Until the

early 1960s the street market was held in a traditional wide open space in

front of

Selfridges’ store by night.

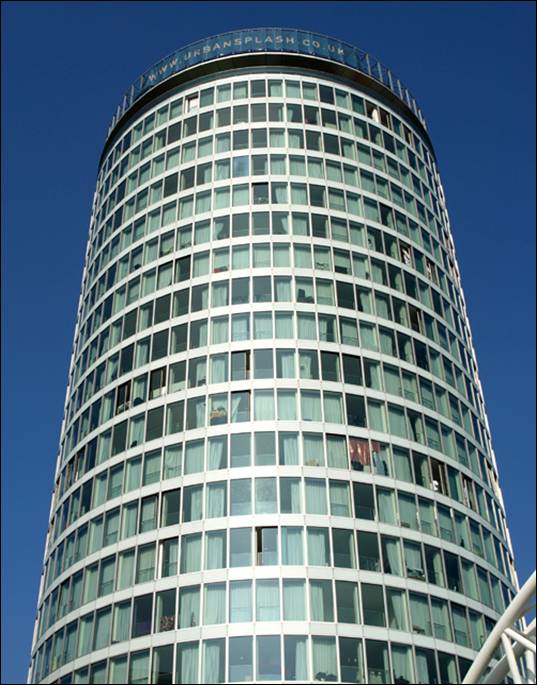

The Rotunda:

It was originally used as offices,

but has now been upgraded and converted to residential use.

Close to the Bull Ring; Moor Street station

concourse. The steam locomotive is

preserved for display purposes.

This is

central

Finest of the city’s railway

stations was Curzon Street, opened in 1838 and terminus of the London &

Birmingham Railway.

(Right) A close-up of the

arms of the L&BR over the main entrance.

The

building survives out of use, but is no longer owned by the railway. Regular passenger trains ceased to use the

station when New Street was opened in 1854, but the building continued in use

as railway goods offices until 1968.

Left:

The Victoria Law Courts in Corporation Street; a remarkable building of ornate

terracotta, opened in 1891. Queen

Centenary Square, looking towards Symphony

Hall, which was completed in 1991 and opened by H.M. the Queen.

The Repertory Theatre is at the extreme right.

Left:

the interior of Symphony Hall, widely

recognised as having one of the finest acoustics in the world.

Right:

the statue in Broad Street, opposite Centenary Square, of the three

eighteenth-century men who were behind

Also in Centenary Square is the new

Library of Birmingham, opened in August 2013.

This remarkable building, with its

reconstructed Victorian Shakespeare Room and its two roof gardens (one is pictured right), replaced

the inverted concrete ziggurat built in

the 1960s and reviled by the Prince of Wales, which in turn had replaced the

much loved Victorian Library.

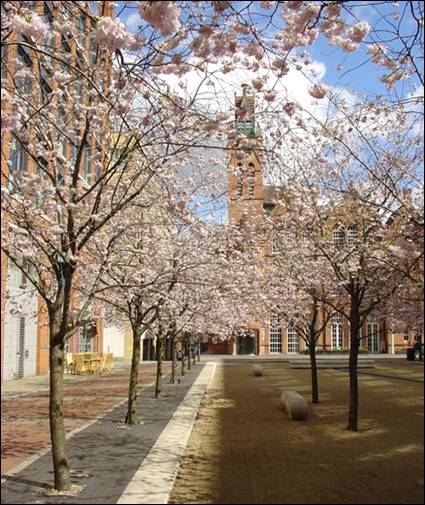

Broad Street, just beyond Symphony

Hall, and (a hundred yards up to the right) Oozells

Street with the ornate Ikon Gallery just discernible

through the Cherry Trees

Birmingham

Canals

The view from Gas Street basin to

the Hyatt Hotel, and an unchanged area by the Worcester Bar

Left:

Pleasure boats on the canal behind Symphony Hall (at the left) with

Broad Street crossing the bridge in the background.

Right:

Surviving older buildings alongside the canal, with the National Indoor

Arena in the distance.

The canal behind Symphony Hall on a

winter’s afternoon and a Spring evening.

The

Edgbaston

and

The

University of Birmingham

Pleasure boats on the

Edgbaston is a

spacious and leafy suburb little more than a mile from the city centre.

The right

hand picture shows part of the

The

Chancellor’s

Court The buildings were

designed by Sir Aston Webb, best known for designing the façade of

The statue of George I, by Jan Van Nost, dating from 1722, outside the Barber Institute of

Fine Art near the University entrance.

The Barber Institute is regarded as

one of the finest small art galleries in

The entrance to the Great Hall, completed in 1909.

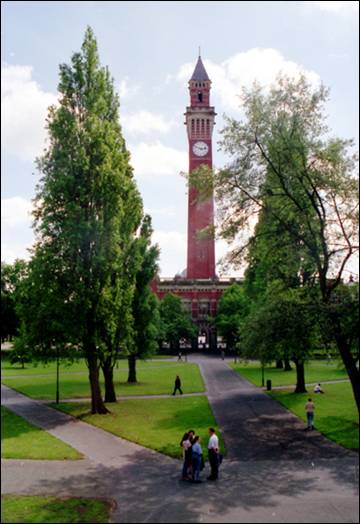

The

photograph explains the origin of the once derogatory phrase “Redbrick”, used

by Oxbridge men about “lesser, provincial” universities. In the early years of the war

Left:

“Old Joe”, the university clock tower, named after Joseph Chamberlain

who was the driving force to establish the university and who was its first

Chancellor. The tower is 325 feet high

and modelled on the Torre di Mangia

in Sienna.

Right:

The Vale, part of the university’s extensive campus. This land formed the grounds of private

residential property until acquired by the university after the war.

Continuing south-westwards down the Bristol Road:

A little further down the Bristol

Road from the University: Selly Manor in

Bournville.

Parts of the building date back to 1327.

The suburb of Bournville

was developed in the 1890s by the Quaker Cadbury family as a “model village”

for employees of their chocolate factory.

The houses, built in the Arts and Crafts style, remain much

sought-after, particularly by university staff.

The Lickey

Hills on

The hills,

once property of the Earls of Plymouth, were acquired by the city between 1888

and 1920. To the left enthusists fly kites with a view over the city beyond. The other photograph faces in the opposite

direction, with views across Worcestershire, over Bromsgrove and the

Birmingham

Industry

and

the

Jewellery

Quarter

Left: Where

world industrialisation first began – Soho House, the home of Matthew Boulton from 1766 to 1809.

Right:

Boulton, William Murdock, Erasmus Darwin,

Joseph Priestley, Josiah Wedgwood, William Withering and James Watt were the

architects of the Industrial Revolution.

They called themselves the Lunar Society and met at Soho

House to discuss scientific projects and the development of modern means of

manufacture. The society was so named

because, in the days before street lights, they met at full moon to take

advantage of the moonlight when walking to and from Soho

House.

Soho Manufactury was built nearby

and supplied fine ware to many of the Courts of Europe.

The Chamberlain Clock, erected in

1903 at the junction of Warstone Lane, Vyse Street and Frederick Street. Joseph Chamberlain was at one time M.P. for

the district.

Caroline Street: a Georgian building with an elegant portico,

still in use as a workshop.

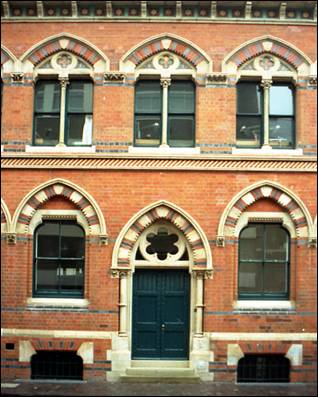

Attractive brickwork on the façade

of this jewellery works in Vittoria Street.

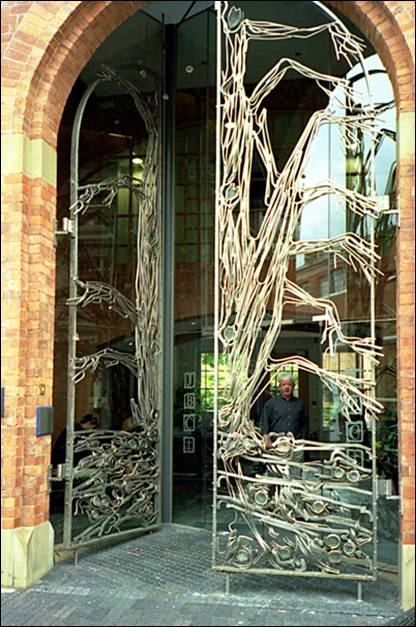

The

permanently open (i.e. “welcoming”) gates of the Jewellery Business Centre,

commissioned by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales in the 1990s and sculpted in steel

and brass with glass ‘jewels’. The

initials of the Centre can be seen within the doorway, set out in hallmark

style, with the customary

Right:

A traditional Birmingham street sign in the Jewellery Quarter.

Vyse Street, with various local

jewellery ‘outlets’ to tempt the buying public and, at the right, the recently

opened Jewellery Quarter railway station, largely obscured by the 19th

century gentlemen’s urinal, made in Glasgow from cast iron.

The

Stately Homes of

Birmingham

A couple of miles from the city centre

takes one to Aston Hall, built in 1634 for Sir Thomas Holte. It was

acquired in 1818 by James Watt jnr but was bought by

Birmingham Corporation as a museum in the 1850s. The interior contains a particularly

impressive Long Gallery (right).

On the eastern fringes of the city is Castle Bromwich Hall, a Jacobean mansion completed in

1585, and once a seat of the Earls of Bradford.

The hall is privately owned and not open, but

the gardens include the last surviving baroque garden, to which the public is

admitted.

= = =

= =

My memories of childhood in

Site hits since 10th October 2007: